What is uveal melanoma?

A choroidal melanoma (malignant uveal melanoma) is a rare, malignant eye tumour that has developed directly in the eye and almost always develops on one side only. Because it develops directly in the eye, choroidal melanoma must be distinguished from other forms of tumours that first appeared in other parts of the body and then developed metastases in the eye. Although choroidal melanoma is rare, it is one of the most common malignant tumours that originate in the eye. People in the white population between 50 and 70 years of age are more likely than average to develop choroidal melanoma. The tumour may have already grown through the layers of the eye and/or grown into the neighbouring tissue. It is also not uncommon for choroidal melanoma to metastasise to other parts of the body.

How does a choroidal melanoma develop?

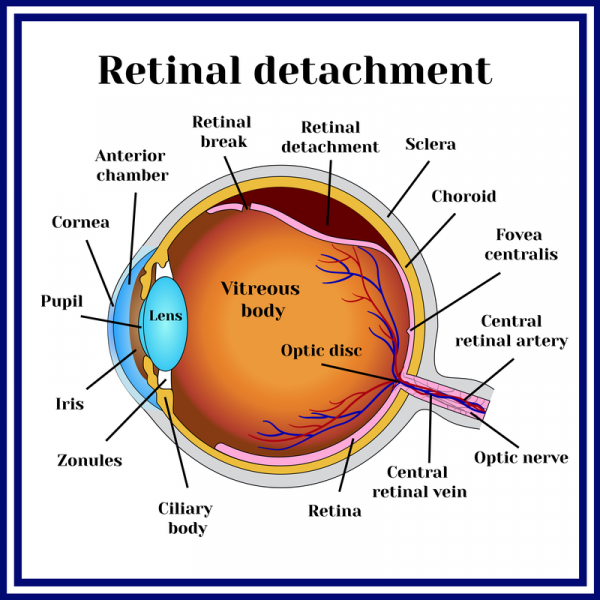

A choroidal melanoma forms from the pigmented cells of the choroid, which multiply unchecked. In addition to the retinal blood vessels, the choroid serves to nourish the eye and is a dense network of fine blood vessels. It is located between the sclera and iris of the eye. Another subtype of choroidal melanoma develops between the iris (about 5%) or in the ciliary body, the point where the lens is suspended (about 10%).

The exact reasons for the development of uveal melanoma are not yet known. However, people with a mole in the choroid (choroidal nevus) and people who suffer from the congenital disease neurofibromatosis are more likely than average to develop choroidal melanoma. Furthermore, it is suspected that UV radiation can play a role in the development of choroidal melanoma. The increased occurrence of pigment cells in the eye (ocular melanocytosis) and genetic mutations of the GNAQ/GNA11 genes are also suspected of causing choroidal melanoma.

What stages is choroidal melanoma classified into?

A uveal melanoma is divided into stages 1 to 4. If it is a localised choroidal melanoma of stages 1 to 3, the tumour is usually removed surgically. If the tumour can be removed completely, the chances of recovery increase. In the case of a stage 4 tumour, the patient can also still be cured, provided that only individual metastases are present. However, patients with stage 4 cancer have a shorter life expectancy. In many cases, the attending physician only prescribes palliative treatment methods to relieve the patient's pain. This may include immunotherapy, which can extend the patient's life expectancy.

What symptoms indicate choroidal melanoma?

Some choroidal melanomas show no detectable growth over a long period of time, while in most cases, however, a choroidal melanoma grows steadily, destroying the retina over time. Patients therefore often complain of deteriorating vision. If the tumour has led to detachment of the retina, a reduced field of vision, including obscured vision (scotoma), is also possible. Many patients complain of flickering, flashes or double or blurred vision or headaches. However, these symptoms of choroidal melanoma usually only appear at an advanced stage. Since choroidal melanoma does not cause any symptoms for a long time, it is usually discovered by chance.

A uveal melanoma can also metastasise to other parts of the body. This is the rule in about 30 percent of all cases. Above all, the liver, bones and lungs are affected more often than average. Symptoms of paralysis, reduced performance and/or pressure pain in the affected regions can be the first signs of metastatic spread. At the time of diagnosis, however, choroidal melanoma has metastasised in only a few patients, which may also be due to the fact that they are still quite small at the beginning and are easily overlooked. Even after successful treatment of uveal melanoma, metastases can still occur in other parts of the body years later.

How is choroidal melanoma diagnosed?

Most of the time, choroidal melanoma is diagnosed rather accidentally during a routine examination by an ophthalmologist. Through the so-called indirect ophthalmoscope, an ophthalmoscope that is either worn on the head, as a slit lamp or as a pair of glasses, the ophthalmologist can visualise the back of the eye and thus see an existing tumour and its extension through pigmentation or typical signs of growth. To confirm the diagnosis, the ophthalmologist can also perform an ultrasound examination (echography). This is done using a small ultrasound probe that directs a beam of sound directly at the tumour. This sound beam is reflected, recorded by an acoustic echo and displayed on a monitor. If a choroidal melanoma is present, typical figures can be recognised in the sonic echo.

In addition to the ultrasound examination, the ophthalmologist can also perform an optical coherence tomography (OCT). This is a laser that scans the retina and choroid while a point of light is fixed. However, fluorescence angiography (FAG) can also be used, in which a dye (fluorescein) is injected into the patient's arm vein and reaches the blood vessels in the eye after about 20 seconds. FAG is used to visualise the blood flow in the eye as well as the utilisation of the blood vessels. The resulting images can show the ophthalmologist whether a choroidal melanoma is present.

How is choroidal melanoma treated?

A choroidal melanoma must be treated. If the tumour remains untreated, it may not only lead to the destruction of the eye. The risk of metastasis also increases dramatically. The type of treatment always depends on the stage of the tumour.

More than 100 years ago, it was still common to remove the eye (enucleation) in the case of choroidal melanoma. For about 40 years, however, choroidal melanoma has been treated with targeted radiation, which has since become the most common form of therapy. In this way, the tumour can be destroyed and the eye can be preserved. However, depending on the size of the tumour and its location, the ability to see may be impaired. Radiotherapy for choroidal melanoma can be given in three different forms:

- Brachytherapy: In this form of radiotherapy, small radiation beams are sewn onto the outside of the sclera on the affected eye during an operation. The prerequisite for this is, however, that the tumour is smaller than 6 mm and that it can be reached with the radiation carrier. After successful treatment, the radiation carrier is surgically removed.

- Proton therapy: This radiation therapy can be used for larger choroidal melanomas or if they are close to the macula, the sharpest point of vision, or the optic nerve head (papilla). In contrast to brachytherapy, this type of irradiation takes place from the outside with protons. The treatment depends on a technically extremely complex system (cyclotron).

- Radiosurgery: This type of irradiation uses a very high dose of targeted gamma rays.

In addition to radiation, the tumour can in principle also be removed surgically under certain circumstances. In addition to the patient's general state of health, the location and size of the tumour is also of decisive importance. As a rule, large tumours with a small tumour base are well suited for surgery. Prior to surgery, radiation is administered to kill the tumour and prevent the tumour cells from metastasising to other parts of the body during surgery. Within the surgical procedure, the dead tumour tissue is then removed, increasing the likelihood of preserving vision.

When is there a risk of metastasis?

Not every choroidal melanoma necessarily forms metastases. However, the Charité Hospital in Berlin has been able to identify some risk factors that increase the danger of metastasis. In addition to clinical aspects such as tumour location and size, these include tumour boundary and the histology of the uveal melanoma, such as the presence of vascular loops and/or certain genetic factors.

What is the prognosis for uveal melanoma?

The prognosis for choroidal melanoma is generally good, although there is no absolute guarantee that the tumour will be completely destroyed or that vision will be preserved. The respective form of treatment has no influence on the patient's probability of survival. Possible metastases, which can also occur after the removal of the tumour, have usually already formed before the treatment and are therefore to be evaluated independently of the form of therapy.

In the majority of cases, the choroidal melanoma is damaged or (completely) removed by treatment. Since the complete destruction or removal of the tumour is not always successful, the choroidal melanoma can recur after treatment. Patients should therefore attend regular follow-up examinations over a period of at least 10 years to check the affected eye for tumour remnants or tumour regeneration.

The prognosis for a diagnosis of uveal melanoma always depends on various factors such as the size of the tumour, the stage of the cancer, but also the cell type. At the time of initial diagnosis, metastases are usually present in just under 1 % of patients. However, since metastases form in other organs in 30 % of all cases, the prognosis always depends on whether the daughter tumours could also be completely removed. If this is the case, the chances of survival after choroidal melanoma are good. The 5-year survival rate is about 75 %.

What is the aftercare for uveal melanoma?

After treatment of uveal melanoma, it is advisable to have regular check-ups with an ophthalmologist every six months or so. Since the risk of metastasis remains even after successful treatment, the patient should also have his or her liver examined at intervals of three to six months. The liver in particular is an organ in which metastases can also form with a time delay.