What is CUP syndrome?

CUP syndrome stands for "Cancer of Unknown Primary". In German, CUP means "cancer with an unknown primary tumour". Doctors understand this cancer disease with an unknown primary tumour to mean that tumour metastases can be identified, but the site of origin of the cancer itself cannot be determined in the body. The CUP syndrome is ultimately discovered because of its symptoms, or during a routine examination. About two to four percent of all cancers can be attributed to CUP syndrome.

How is it that the site of origin of the cancer cannot be found immediately?

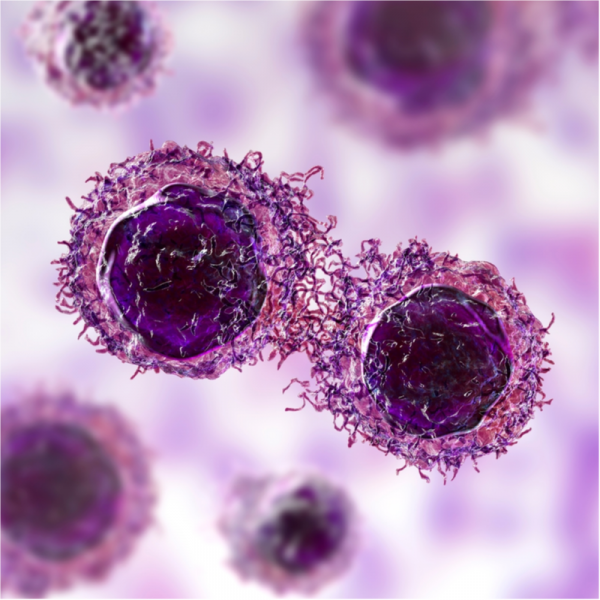

The site of origin of a CUP syndrome cannot usually be identified because the tumour is too small and the usual diagnostic imaging methods cannot detect it. This is mainly because the stem cells of the primary tumour divide so slowly and thus virtually do not multiply on the spot. This means that uncontrolled cell growth is simply not detected. However, via the bloodstream or the lymph nodes, for example, metastases form in other organs and grow much faster there, which ultimately leads to a recognisable tumour.

Another reason why the original focus cannot be found immediately is that the primary tumour is no longer present at the time of diagnosis. This can be the case, for example, with so-called spontaneous remission. Spontaneous remission means that the primary tumour has been defeated by the organism, for example, after it has formed metastases.

In patients in whom the primary tumour has been found, the site of origin is the lung in 20 to 30 percent of all cases, followed by the pancreas with 10 percent. But it can also be found in almost all other organs, albeit with less frequency. On the other hand, organs such as the mammary gland, the colon or the prostate, where tumours otherwise often develop, are rather unlikely to develop a CUP syndrome.

What are the symptoms of CUP syndrome?

The symptoms of CUP syndrome depend not only on the spread of the cancer and the amount of tumour cells, but also on which organs are affected. If the CUP syndrome is far advanced, the patient usually complains of rather unspecific symptoms such as tiredness, general fatigue, loss of appetite and an unwanted loss of weight.

If, on the other hand, CUP syndrome is localised to one organ, the following symptoms may occur:

- bulky swelling, for example, if the lymph nodes are affected,

- circumscribed pain, if the bones are affected,

- Coughing and/or difficulty breathing if the lungs are affected,

- Headache, nausea and vomiting as well as the loss of certain brain areas in the case of metastases in the head,

- Ascites, accompanied by an increase in the circumference of the abdomen and problems with deep breathing if the peritoneum is affected,

- Pleural effusion associated with shortness of breath and difficulty breathing when the pleura is involved.

How is CUP diagnosed?

Often, the metastases of CUP syndrome are not noticeable for a long time and are diagnosed purely by chance, for example during a routine examination. In any case, however, the treating doctor will want to identify the primary tumour if he or she suspects a CUP syndrome, for which the following examinations are usually carried out:

- a thorough physical examination,

- Blood tests,

- taking a tissue sample from the metastasis to perform a biopsy,

- standard imaging procedures, such as an X-ray and/or ultrasound examination, a computer tomography (CT), a positron emission tomography (PET) and/or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Based on the tissue sample, the doctor learns something about the type and appearance of the tumour cells, which in turn ultimately gives him or her information about the type of tumour. Special stains that show certain types of cells in a certain colour can also reveal what type of tumour it is. In most cases, the results of the tissue sample are decisive for the subsequent therapy.

How is CUP syndrome treated?

As with other cancers, CUP syndrome can basically be removed by surgery and/or treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy or hormone therapy. So-called supportive therapy, which includes, for example, pain therapy and treatment of nausea etc., can also make the patient's life easier. The type of therapy used always depends on what kind of tumour tissue the biopsy was able to detect. But the localisation of the tumour and its size as well as the patient's general state of health are also decisive for the treatment.

If the metastases are localised, they can either be removed surgically or treated with radiation. If there are several tumour sites, chemotherapy is often administered. In the case of colon, liver, lung or kidney cancer, targeted treatments can be ordered, which are based on tyrosine kinase inhibitors (tablets) or antibodies (infusions). However, these targeted therapies for CUP syndrome are still in the trial phase. If, on the other hand, the metastases are painful, radiotherapy is often ordered. For metastases that have affected the bone, treatment with bisphosphonates, i.e. drugs to strengthen the bone, or antibodies (Denusomab) is usually given.

If a large number of metastases have already formed, or if the patient is in a rather poor state of health, the doctor will design the treatment to keep the patient pain-free and improve his or her quality of life. In this case, the cancer is usually incurable and the patient should, if possible, be able to enjoy his or her remaining time.

What is the prognosis for CUP syndrome?

Since CUP syndrome has very different clinical pictures, its life expectancy is also very individual. The prognosis can therefore range from a possible cure to a life expectancy of a few weeks or months.

On average, life expectancy is between 6 and 13 months. One year after diagnosis, only about 25 to 40 percent of all patients are still alive. In rather rare individual cases, patients live for more than 5 years after diagnosis.